The Vital Importance of FOSS: The GNU/Linux Operating System

Alexandre DesAulniers | November 2023 | PDF

Abstract

The GNU/Linux project, founded on the principles of free and open-source software (FOSS), has become a cornerstone of modern technology. This paper explores the historical development of GNU and Linux, their underlying “free and open source” licensing models, and their far-reaching impact across various domains. Key findings demonstrate the critical role of GNU/Linux in driving innovation in software development, mobile computing, cloud infrastructure, and scientific research.

While open-source software offers significant advantages, the importance of proper maintenance for security is emphasized, and has been put into question. The paper concludes by highlighting the enduring significance of GNU/Linux as a catalyst for global collaboration, accessibility, and technological advancement.

List of Figures

-

Figure 2: Global mobile operating system market share (Statista Research Department, 2022)

-

Figure 3: Android internal open-source software stack (Alphabet Inc {Google}, 2023)

-

Figure 4: Typical Layers of Cloud Computing Infrastructure (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008)

Lists of Tables

1. Introduction

The GNU Project, founded in September 1983, and the Linux Kernel/Operating System, launched in 1992, stand today as global cornerstone technologies. Both projects have spearheaded the adoption of free-and-open-source software, designs, licenses, and hardware (Stallman, 2023). The GNU/Linux project is widely used in everything from manufacturing to scientific research and home appliances alike. The GNU/Linux operating system is a technology that lies in the shadows, one that is not usually user-facing. Our world relies on GNU/Linux to be dependable and keep global software infrastructure online (The Linux Foundation, 2022).

Both projects rely on individual and corporate contributors to aid in development, whether that be via software development, bug fixing, promotion of technology, enforcement of license terms, or general education about how to utilize free and open-source software (Peters & Ruff, n.d.). The GNU/Linux project’s core mission is to be free, accessible, and to continue to foster free and open-source future development.

2. Technical Background

2.1 What is FOSS, and what are the GPL/MIT licenses?

The fundamental principles of free and open-source software (FOSS) stem from the licenses that support its development and defend it. In modern day, there are many licenses that an author can choose to use to write protected FOSS, but they mostly stem from two pioneer open-source licenses. Known as the MIT license, and the GPL license, both were built incrementally over the late 1980’s by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Richard Stallman/The GPL Project, respectively. The MIT license does not have a firm date of introduction, but many argue the license was solidified in 1985 given by dated copyright years, and development time (Saltzer, 2020). The GNU GPL v1.0 was launched in 1989 but had been in incremental development since the beginning of the GNU project in 1984 (Tai, 2001).

Both licenses had the same end goal of enabling open-source projects to be legally backed, however, both licenses have key differences. The MIT License has very few restrictions on redistribution, and most importantly, has no restrictions on commercial use. The MIT license is what is known as a permissive license, as anyone may do whatever they would like with the original licensed work, as the software is provided as is, with no support or warranty. (Saltzer, 2020). On the other hand, the GPL license is known as a restrictive license. The GPL license allows for licensed code to be sold, however, mandates that the customer has the right to access and modify the source code. It also mandates that if the code is modified and redistributed, it must also use the GPL license (Free Software Foundation, 2023).

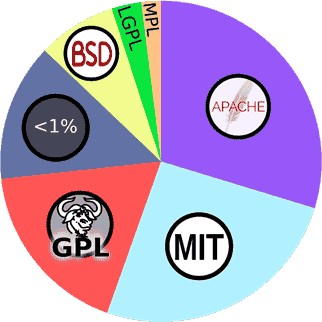

Figure 1: Usage chart of common open-source licenses in 2021 according to security and open-source compliance auditor firm mend.io (Rjjiii & Wikimedia Commons, 2023)

2.2 Linux’s Origins in UNIX

Developed throughout 1969-1971, by AT&T, UNIX was a popular operating system choice at the time, used by many across North America and Europe. UNIX is a closed source operating system, meaning that the purchaser of the UNIX software license was not entitled to see the source code and inner workings of the UNIX kernel, nor any associated UNIX software (McIlroy & AT&T Bell Laboratories, 1987).

Initial work began on the Linux V0.01 kernel in early 1991, led by sole programmer Linus Torvalds. Torvalds had envisioned a free UNIX like operating system, with high program compatibility (Stallman, 2021). As many of the components required to build such an operating system were already freely available, Linus began work on the Linux kernel project, borrowing philosophies and GPL licensing from the GNU project. Linux was tied tightly to the GNU project, having substantial portions of GNU software and GNU components included in most Linux based operating systems (Stallman, 2021). Linus was able to expedite much of his initial work, thanks to pre-existing GNU Project open-source code, knowledge, and existing licensing. Linux now exists as a base kernel, frequently used with additional GNU applications.

2.3 Operation, Protocol and Maintenance of the Linux kernel and GNU project

The Linux project falls under a GPL style license (Stallman, 2023), and by being an open-source project at such a magnitude, requires an exceptionally large maintainer base. As of Linux kernel version v4.7 (released 24th of July 2016) there were approximately 1600~ active developers, and since 2005, more than 13,500 individual developers have contributed code to the Linux kernel (Peters & Ruff, n.d.). To manage the Linux project with the current level of contributors, many levels of administration have been set up to meticulously organize and approve contributions to the project. This is like any other large scale open-source project, and most follow a similar hierarchy (Peters & Ruff, n.d.).

2.4 Contribution to the GNU/Linux Project

There are many roles that partake in the contributing to the GNU/Linux project, and each role has their own significance (Peters & Ruff, n.d.). Large scale open-source projects such as GNU/Linux have large supporting communities that equally take part in democratically contributing and electing project leaders (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023). The open-source philosophy states that anybody can be a contributor to an open-source project, granted that they follow the project’s governance structure properly (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023).

Table 1: Table of Linux Kernel contribution administration levels (adapted from Peters & Ruff, n.d)

| Role | Responsibility | Who |

| Project Leader | The Project Leader is responsible for making the final decision in disputed decisions related to the kernel, and to manage project maintainers and any associated project committees. They are also the face of the project. | Currently, Linus Torvalds. When it comes time to decide on a new project leader, the project leader, along with the community will come together to select a new project leader. |

| Project Maintainers | Project maintainers are tasked with auditing contributions. If there is disagreement, maintainers report to the project leader and community. The project leader will have the final say. | Project maintainers are usually highly trusted, long-time committers, who have been chosen to manage specific branches of the Linux project. |

| Project Committers | Project committers are commonly trusted, long time kernel contributors, who can directly contribute code to the project, usually without audit. | While project committers are highly trusted contributors, contributions can still be subject to review by a project maintainer, or a project manager. The maintainer, or the leader will have the final say. |

| Project Contributors | Project contributors are those who decide to contribute code to the Linux Kernel, whether that be new feature development, or a bug fix. | Anybody can be a Linux/GNU contributor, but untrusted contributors must have their code/addition audited by a project maintainer prior to a merge. Code can be rejected. |

| Users | Users do not contribute directly to development of the kernel, but indirectly contribute by using, promoting, providing feedback, and suggesting new ideas. | Anybody can be a user. Users have the most power in Linux development, as they can oust anybody above them, if there is a consensus of dislike, bar the project leader. |

3. Societal Impacts

3.1 Importance of the Open-Source Philosophy, and of the GNU/Linux Project.

As said by The Linux Foundation (2022) “Linux is an operating system that is ‘by the people, for the people.’” (p.5). Free and open-source software guarantees that any individual has the right to do whatever they would like with the program. They may modify it for their particular use case, redistribute it, and have full transparency on the innerworkings. By being associated with a free and open-source license, it can protect software from abusive corporations and other general copyright abuse (Stallman, 2023)

Free and open-source software allows the communities that rely on it to have flexibility on how they use the piece of software. (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023). Often, this flexibility leads to community members finding flaws with the original work. The flexibility that the FOSS model brings allows that group to contribute back to the project to have the issue fixed for others (Peters & Ruff, n.d). Different communities have different motives for contributing to the same open-source software, however, it will always end up benefiting the entire project. GNU/Linux has a large commercial contributor backing, as many corporations depend very heavily on the operating system (Peters & Ruff, n.d). Many will contribute to better improve GNU/Linux for their use case, but these contributions will end up benefiting the entire project. GNU/Linux also has a large individual contributor population, as many use the operating system for personal projects, and discover issues in their own use cases (Peters & Ruff, n.d).

3.2 Current Global Importance of the Open-Source Philosophy.

At its core, open-source software encourages collaboration, and conversation. Instead of countries, individuals and organizations all competing against each other to develop software and hardware, the open-source philosophy encourages global collaboration and community involvement (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023). Groups, whether that be governments, corporations, or individuals, all may have differing end goals, but all require the same building blocks, with thousands of eyes constantly combing through them. In the context of global security, this is a huge benefit. Everybody is inclined to make the software they use as secure as possible, and by contributing, they in turn make the software more secure for the entire open-source community (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023).

3.3 Can We Trust Open-Source Software?

With the nature of open-source code, there will always be a concern of security. (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023). Globally, many companies are heavily dependent on the use of open-source software and rely on it to be secure. While the inner workings of an open- source project will be available for a potential bad actor to exploit, there have been mixed findings regarding the security effects of that project, and whether that open-source is a net positive. According to Gao (2020), “a larger user base of software products provides malicious agents, such as cyber hackers, more opportunities to exploit software vulnerabilities.” With a larger install base, a piece of software is more prone to being exploited. If there is a large community, and corporate backing to support a piece of open-source software, it is a given that there will be more contributors and committers looking over a project. (Peters & Ruff, n.d). If a piece of open-source software, such as GNU/Linux is properly maintained, and has adequate project contributors, it will be more secure in comparison to a closed source equivalent. This is due to having a larger number of contributors, all with differing goals. However, the contrary is also true. Depreciated and unmaintained open-source software can be and has been proven to be a huge security risk (Gao, 2020).

4. Current and Potential Applications of GNU/Linux

4.1 The Importance of GNU/Linux in Mobile Computing

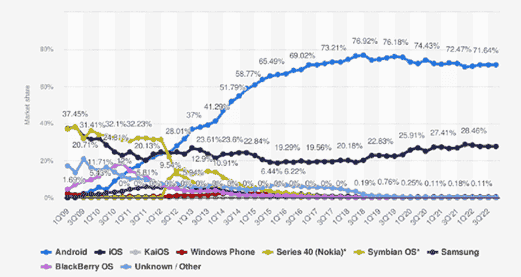

GNU/Linux, and the open-source model have both proven to be extremely important in the mobile computing industry. One of open-source’s largest successes in mobile computing would be the Android project. According to Statista Research Department (2022), globally, approximately 71.6 percent of all mobile devices run a variant of the Android ASOP project.

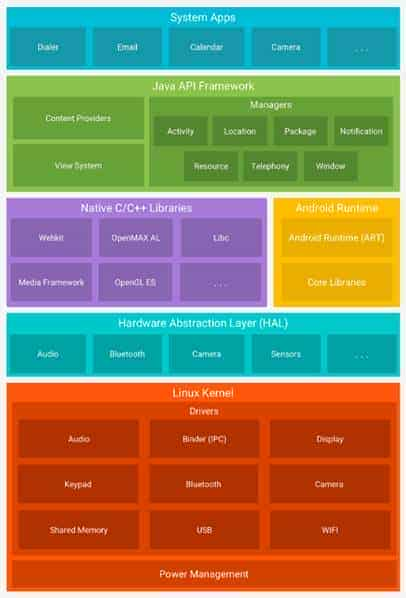

While many companies that use the Android project, such as Google, add additional closed source modules on top of the ASOP (Android Open-Source Project), the ASOP at its core is an open-source project, built on open-source modules such as the Linux kernel, and the FOSS Java API frameworks (Alphabet Inc {Google}, 2023). The Linux kernel has allowed for ease of hardware development for Android, allowing developers to develop hardware drivers for software that is otherwise industry standard, and that they are familiar with (Alphabet Inc {Google}, 2023). Hardware support for a specific device can also be up streamed into the mainline Linux kernel. (Peters & Ruff, n.d.). Most software components from the AOSP fall under the Apache 2.0 license, which is another quite common GPL like open-source license, and specialized versions of the GPLv2 (Alphabet Inc {Google}, 2023).

Figure 2: Global mobile operating system market share (Statista Research Department, 2022).

Figure 3: Android internal open-source software stack (Alphabet Inc {Google}, 2023).

4.2 Importance of GNU/Linux in Large Scale / Cloud Computing

Linux and open-source software plays a huge role in datacenter use, and in keeping the cloud computing infrastructure our world relies on operational. The Linux operating system is used as a base by most of today’s cloud computing and software-as-a-service vendors. (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008).

Figure 4: Typical Layers of Cloud Computing Infrastructure (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008).

GNU/Linux is typically responsible for individual server component management, and networking solutions are built on top of the Linux kernel to network adjacent servers in a datacentre environment (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008). Using industry standard open-source virtualization software, Linux can provide a stable, and constantly up to date solution for datacentre managers to consolidate infrastructure. GNU/Linux components are frequently used on all levels of server management, shown in the above figure. It allows cloud computing vendors to be flexible in terms of the services they can offer (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008).

Cloud computing vendors often offer software-as-a-service, known as SAAS, which is used to run apps, websites, streaming services, internet messaging services, and much more (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008). SAAS applications are typically built on top of a Linux environment. Linux is typically used to provide platform-as-a-service (PAAS) and infrastructure-as-a-service (IAAS), which are both more complete cloud solutions which aim to deliver a complete server environment to a customer, with IAAS being a more complete version of PAAS (Mohammed & Zeebaree, 2021). All three are crucial to modern hosting, and large-scale server deployment. GNU/Linux can offer infrastructure management, support for customer facing virtual environments, and the software base necessary to provide SAAS, PAAS, and IAAS solutions to customers (Jones, M. & IBM Developer {IBM}, 2008).

4.3 Importance of GNU/Linux, and FOSS in Science and Education

FOSS software plays an ever-increasing role in modern research, scientific development, and education. (Smith et al., 2018). FOSS, and the GNU/Linux operating system have been heavily used in education to fill learning gaps and teach practical software development. (Lertnattee et al., 2022). Devices such as the Raspberry Pi, which is a small and affordable GNU/Linux computer have been extensively used in education and small-scale projects due to cost, flexibility, and size (Staple, 2023).

The Raspberry Pi platform has been used as a tool to assist in teaching coding to students across the world, due to the accessibility of the platform (Karthikeyan et al., 2023). Students, researchers, businesses, and hobbyists use the GNU/Linux operating system, and Raspberry Pi platform to build projects for education, income, and scientific research. Publications such as the Journal of Open-Source Software (JOSS), have aimed to consolidate journal articles and research papers covering various open-source scientific projects, to make information freely and widely available for scientific and reference use (Swarts, 2018; Smith et al., 2018).

Journals such as JOSS have allowed free and open-source projects to have an academic acknowledgement, and reference point. This has allowed FOSS software to overcome academic citation hurdles, and the creation of formal project documentation (Smith et al., 2018). GNU/Linux has been used as an educational tool to introduce programming and scientific software into fields that have traditionally not required it, such as healthcare, and has been used to better student understanding, and carried forward as a tool in the healthcare workplace (Lertnattee et al., 2022).

GNU/Linux is frequently used in research, due to flexibility, robust programming and scientific software support. GNU/Linux can also be used as a base to create large supercomputing clusters, needed for large research datasets. The Linux kernel provides a platform for researchers to create high performance grouped network computing software, which can be configured extensively to meet computing requirements needed by a particular kind of research, and can easily scale to meet increasing requirements, or already vast datasets. (Phillips, 2020).

5. Conclusion

Across all industries, The GNU/Linux operating system and FOSS software has proven to be dependable, secure if properly maintained, and crucial to many tasks (The Linux Foundation, 2022). By being open source, it can allow an individual or organization to modify the source software to their needs, and not have to worry about legal repercussion, if licensed properly (Saltzer, 2020; Stallman, 2023). The open-source philosophy will always encourage collaboration, community involvement, and democracy to thrive (Mangnani & Sakharkar, 2023), and will continue to be a crucial, and necessary tool for science, research, education, industry, and innovation (Karthikeyan et al., 2023).

References

Alphabet Inc [Google]. (2023). Platform architecture. Android Developers. https://developer.android.com/guide/platform

Alphabet Inc [Google]. (2023). Content license. Android Developers. https://developer.android.com/license

Clemente, D. C. (2004, February). Linux circular kernel map [photograph]. Adapted from https://www.danielclemente.com/amarok/

Free Software Foundation. (2023, June 11). The GNU general public license v3.0. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.html

Gao, X. (2020). Open source or closed source? A competitive analysis with software security. Decision Analysis, 17(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1287/deca.2019.0390

Jones, M. & IBM Developer [IBM]. (2008, September 10). Cloud computing with linux. IBM Developer. https://developer.ibm.com/tutorials/l-cloud-computing/

Karthikeyan, S. P., Aakash, R., Cruz, M. V., Chen, L., Ajay, V. J. L., & Rohith, V. S. (2023). A systematic analysis on raspberry pi prototyping: Uses, challenges, benefits, and drawbacks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 10(16). https://doi.org/10.1109/jiot.2023.3262942

Lertnattee, V., Pamonsinlapatham, P., & Oniam, W. (2022). A course design and a flexible platform for learning programming languages in health informatics courses. Faculty of Pharmacy, Silpakorn University. https://doi.org/10.1145/3568739.3568808

Mangnani, H., & Sakharkar, P. (2023). Open-Source software –Benefits and drawbacks. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology. https://doi.org/10.48175/ijarsct-11689

McIlroy, M. D. M. & AT&T Bell Laboratories. (1987). A research UNIX reader: Annotated excerpts from the programmer’s manual, 1971-1986. Programmer’s Manual, 139. https://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~doug/reader.pdf

Mohammed, C. M., & Zeebaree, S. R. M. (2021). Sufficient comparison among cloud computing services: IAAS, PAAS, and SAAS: A review. International Journal of Science and Business, 5(2), https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.4450128

Peters, S., & Ruff, N. (2023). Participating in open source communities. The Linux Foundation. https://www.linuxfoundation.org/resources/open-source-guides/participating-in-open-source-communities

Phillips, L. (2020). The Scientist’s Linux Toolbox » Linux Magazine. Linux Magazine. https://www.linux-magazine.com/Issues/2020/241/Scientist-s-Toolbox

Rjjiii & Wikimedia Commons. (2023, January 22). File:Open-source-license-chart.svg - wikimedia commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=128017500

Saltzer, J. H. (2020). The origin of the “MIT license.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 42(4), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1109/mahc.2020.3020234

Smith, A. M., Niemeyer, K. E., Katz, D. S., Barba, L. A., Githinji, G., Gymrek, M., Huff, K. D., Madan, C. R., Mayes, A. C., Moerman, K. M., Prins, P., Ram, K., Rokem, A., Tracy, T., Guimerà, R. V., & VanderPlas, J. T. (2018). Journal of Open-Source Software (JOSS): design and first-year review. PeerJ, 4, e147. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.147

Stallman, R. (2021, November 2). Linux and the GNU System. The GNU Project. https://www.gnu.org/gnu/linux-and-gnu.html

Stallman, R. (2023, July 23). About the GNU project - GNU project - free software foundation. The GNU Project. https://www.gnu.org/gnu/thegnuproject.html

Staple, D. (2023). Robotics at home with raspberry pi pico: Build autonomous robots with the versatile low-cost raspberry pi pico controller and python. Packt Publishing Books | IEEE Xplore. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10163209/authors#authors

Statista Research Department. (2022). Mobile OS market share worldwide 2009-2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009/

Swarts, J. (2018). Open-source software in the sciences: The challenge of user support. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 33(1), 60–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651918780202

Tai, L.-C. (Andy). (2001, July 4). The history of the GNU general public license. free-soft.org. Retrieved November 15, 2023, from https://www.free-soft.org/gpl_history/

The Linux Foundation. (2022, August 26). What is Linux? Linux.com. https://www.linux.com/what-is-linux/